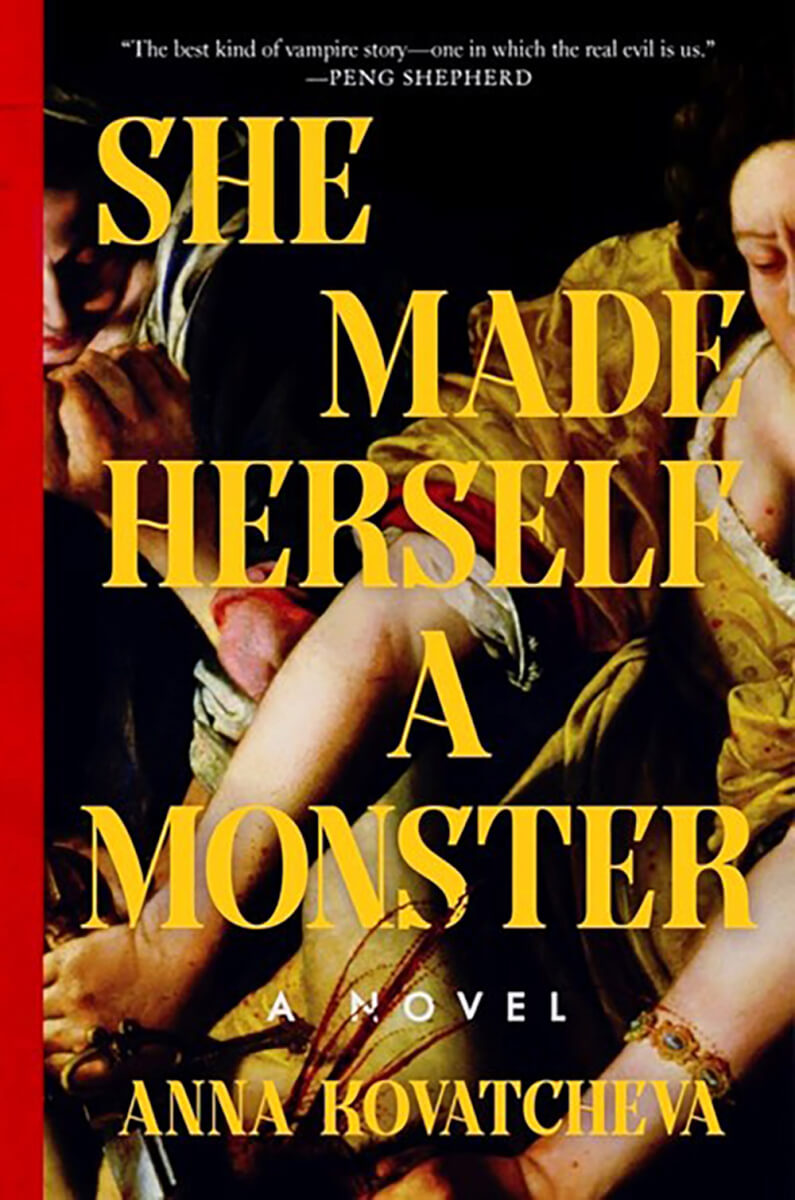

Blood-soaked, heart-stopping and beautifully observed, She Made Herself a Monster is a relentless, transporting story about what happens when a charlatan “vampire hunter” sets up shop in the kind of village of the damned that no outsider will go near.

Yana has plenty of business. In 19th-century Bulgaria, “Every village is haunted in its own way. All of them want her to banish something without form.” The town of Koprivci, renowned for being cursed, is ripe for Yana’s services. Here, the eggs are full of blood, and the children perish. And the villagers, desperate to cast blame and find a cure for their troubles, set their sights on the local widow whom they deem a witch. There are also deeper wounds that a satisfying vampire banishment presumably can’t cure.

The gorgeously rendered, frightening lore of the novel is grounded in wonderfully specific characters and their fraught, messy relationships. Sixteen-year-old Anka is doomed to marry her uncle, who has been waiting for her to reach maturity so he can make her his bride; he was obsessed with her mother before her. She would rather kill herself than go through with it, so she’s been hiding the onset of her period for years. Like Yana’s public exorcisms, Anka’s survival is wrapped in deception and performance. Her cousin Kiril, a young, educated doctor who’s just returned home, despairs of ever finding patients when the villagers would rather believe their ailments are the result of witchcraft. Anka and Kiril both live at the generosity and whims of their powerful uncle, a kind of de facto mayor of their town.

Like many a dark, modern fairy tale, She Made Herself a Monster’s conceits are rooted in history and European folklore, in this case from the author’s birth land of Bulgaria. Anna Kovatcheva cleverly braids traditional elements with her own ideas. For instance, Yana’s ability to perform rites successfully is bound up in her talent for storytelling and performance. As Kovatcheva describes, “in each struggling village that she visits, she stages a grisly tableau in a public square.” Strangely, this well-practiced spectacle instills hope. Tapping into the heritage Yana and the villagers share, “with the stories they know of demons and their slayers, they believe her.”

In this old ritual, there’s something very relatably modern. Kovatcheva weaves together the most vivid of horrors and scalpel-sharp insight applicable to society today.